Don't get carried away with aggregated numerical KPI indicators in quality management

Material prepared by: Scientific Director of the AQT Center Sergey P. Grigoryev .

Free access to articles does not in any way diminish the value of the materials contained in them.

One Russian company on its corporate website announced the formation of a unified product quality management model for all divisions within the company. At the same time, specific numerical goals were named as another example of the ignorance of modern management.

“The results of the work by 2025 should be a reduction to 25% of the costs of eliminating product defects identified at the development and production stage, as well as a halving of the number of unfulfilled contracts due to inadequate quality. This should allow us to form a unified picture of the state of product quality of all organizations within the company and improve the efficiency of quality management systems."

Our team gave a presentation on the importance of fundamental changes in the quality management structure of this group of companies and demonstrated evidence of the lack of knowledge necessary for this in the group of companies using specific examples.

“If you can achieve a goal without a method, then why didn’t you do it last year?”

There is one plus in the declaration - the company openly reported its problems on such a scale. But these problems apparently cannot be solved on our own. Otherwise, why didn't they do it earlier?

“We cannot solve our problems at the same level of thinking that created them.”

The accepted methods of management by goals (numbers) are amazing. It is enough to reduce the cost of eliminating defects by 25% by 2025. Where does this number 25% come from? Why not 23 or 27%? What about the remaining 75%? By what methods?

Does the company currently know about all rework costs incurred in previous periods or only those recorded? Are these only direct costs or taking into account indirect, immeasurable losses? Among the latter are demotivation of workers due to the inability to feel pride in their work, loss of the company’s reputation as a supplier, etc.

Are the company processes that produce defective products in a statistically controlled state? If yes, then only the top management of the company's enterprises can change the situation through systemic changes. If not, there is an urgent need to address special causes locally and bring such processes into a statistically controllable (predictable) state. Only then will it be possible to engage in systemic changes.

Setting numerical targets for unstable (unpredictable) processes is pointless - no one can predict their behavior. Numerical targets for stable processes also do not make sense, since stability indicates a better state of the process with a natural (random) spread of data up and down from the average within +/- 3 sigma in accordance with the rule of thumb for data distribution. These statements are explained in more detail in the open decision "Statistical Process Control (SPC) vs. Standardization of Manufacturing Processes and Operations."

Edwards Deming in his book “Overcoming the Crisis” wrote about the adequate goals of the company:

“Real goals are necessary to optimize the organization as a whole, and not to suboptimize its parts. A goal may sound quite general. A goal without specifying methods for achieving it is meaningless.”

And what about the halving of the number of unfulfilled contracts due to inadequate quality? Is this indicator in a statistically controlled state or not? Why 2 times? How will this value be assessed in the future? By what methods? Here my comments are most likely unnecessary.

How, in general, can someone come up with such goals?

It is surprising that in the first indicator we are talking about reducing rework, specifically rework. Not a word about new methods for improving the quality of the processes that generate these alterations. How are you going to do this? By what methods? How are these methods different from what you did before? Even if such methods were planned, how can one understand, even during their planning, that they will lead to a 25% reduction in the cost of eliminating defects?

What will happen to those rare organizations whose absolute cost of eliminating defects, as a result of successful ongoing work with the quality of all processes, is minimal among all organizations included in the company? They, just like those who did not do this at all, will have to find a way to reduce this indicator by 25%? Not less? Otherwise they will lose this competition?

“Managing by numbers is an attempt to manage without knowing what to do, which in fact usually amounts to managing by fear.”

The main danger is not the declared indicators themselves, but the high probability of their use in the system of compensation (payments) to the heads of the company's organizations. How could it be otherwise in the dominant management style today? The high degree of aggregation of indicators in quality management is another barrier to the search for “upstream” causes. Any aggregated indicator (resultant) hides the signals in the data sources of variability, turning them into noise at the resultant level, thereby depriving personnel of the ability to see the signals in the sources. Finding signals for the presence of specific causes of variability is what needs to be done to improve processes in the first place. At the same time, any reactive actions of management to noise are error of the first kind , only worsening the situation. It is important to understand that at a high level of aggregation, only catastrophic changes will be noticeable in the form of signals (E. Deming). What to do after eliminating or taking control of the sources of special causes of variability, see other materials on our website.

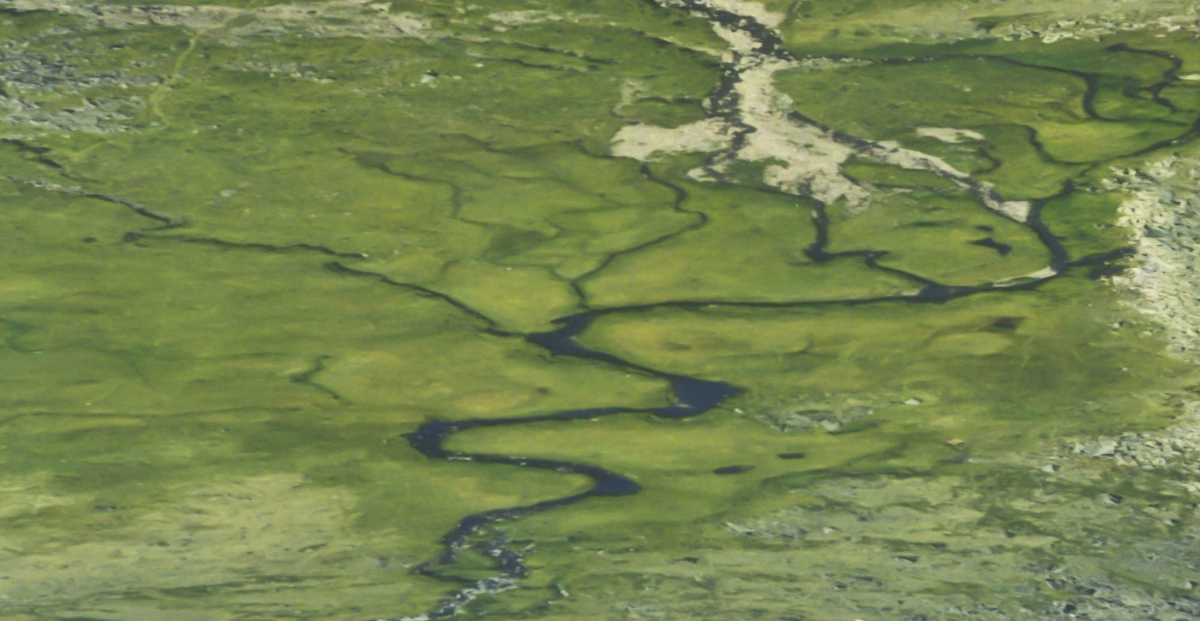

"Upstream search is a powerful lever in solving mixture problems."

Figure 1. Upstream search is a powerful lever in solving mixture problems.

I am sure that the heads of organizations will achieve this indicator (reducing up to 25% of the costs of eliminating product defects). The good thing about management by objectives (MBO) is that there are many evil ways to do this. Here are some examples:

- Without improving the quality of the design and production processes, reduce the volume or share of output of products with the greatest defects.

- Redistribute part of the cost of eliminating defects to other expense items not affected by KPIs.

- Reduce time and costs for developing new products due to reduction of full-scale tests , replacing them with digital model tests.

- Specification tolerances may be expanded or defect definitions may be vague. “It’s good” that the industry does not pay enough attention operational definitions , including defects.

- The so-called “Permit List”, very common in “big” companies, where defects and defects are very expensive. The essence of this method is to give defective products, depending on the degree of defectiveness, the status of products of the 1st, 2nd and 3rd quality classes. All involved departments sign the “Permission Sheet” for each defective part, each of which must sign that this defect is not a defect at all.

In my practice, there was an example when a produced batch was rejected by one quality control inspector, and the next day, another inspector found no reason for rejection and allowed the batch to be shipped to the buyer. So were there any defects or not?

In another example, the head of the quality control department suggested “mixing” defective products into a batch with good ones, thus hoping to reduce the company’s losses on eliminating defects. This could indeed reduce the cost of rework, but would jeopardize further cooperation with the Buyer of the “mixed” batch.

So what is the purpose of such an aggregate indicator as “rework costs”? What will your employees do if their salaries or ratings depend on the value of the indicator? You might argue that you need to work with processes that produce defective products. Yes, I agree. How to work? What to do? How do you know? If you know what to do, why haven't you done it before? In any case, real improvement of processes and technological operations requires new knowledge and time, and salaries can be cut or an employee’s rating downgraded right now. Think about it.

It is a pity that the time and intellectual resources of all levels of company employees will be spent searching for tricks to achieve this indicator using the most accessible methods. This is what usually happens in a management system based on goals or results.

In a conversation with the quality director of a large Russian company, he told me:

- To calculate wages, we do not use all the KPIs we have.

“It’s clear that your employees are ready to sacrifice other KPIs to achieve those for which salaries are calculated,” I answered.

“What can you do, this is Russia,” my interlocutor complained.

- Too general. It is the management of your company that creates these rules of the game, and the workers are forced to adapt if they want to feed their families. The country doesn’t matter,” I explained, as if into emptiness.

"The limitations of "management by objectives" are rooted in numerical norms. "Management by objectives" pays little, if any, attention to the processes and systems in the organization, the potential capabilities of the organization as a whole. As a result, these norms, standards, tasks turn out to be nothing more than , as arbitrary numbers.

As a result of this approach, workers, foremen, and managers find themselves participating in “games”—the need to look good outweighs concern for the long-term interests of the organization. Very often people lose perspective, the purpose of what they do in the workplace."

If you are tired of KPI indicators and ratings, it is better to build Shewhart control charts based on them and analyze them. Using control charts, find out at what level changes are required in the processes that generate your indicators, namely, whether it is necessary to eliminate special causes or make systemic changes.

Develop specific actions, take action, check their effectiveness using a control chart, confirm your assumptions about the selected improvement methods, and if necessary, adjust or abandon them to develop new methods. Here's the Shewhart-Deming PDSA Cycle to help you.

This approach to improvement will be more scientific than any other, will make change efforts truly systemic and measurable, and will help gain real knowledge about your processes.

And Shewhart control charts will allow you to track the results of changes both quickly and in the long term.

Much has been written about the interpretation of Shewhart control charts on our website.

Video 1. Shewhart-Deming Cycle PDSA (Plan-Do-Study-Act, Deming Cycle), which underlies the main standard in the field of quality management ISO 9001, as well as a number of industry standards: IATF 16949 (automotive industry), ISO TS 22163 (IRIS - railway industry), EN/AS 9100 (aviation), GOST RV 15.002 (defense industry), STO GAZPROM 9001, etc. Often referred to as PDCA (Plan-Do-Check-Act).

"When I was first introduced to the concept of the PDSA cycle, within 15 minutes I thought I knew everything there was to know about this model. Now, after decades of active practice and study, I think that someday I will know enough about this concept ".

There are already documented examples of “reducing” the number of rework using method No. 4 of this article: You can expand the tolerance limits of technical requirements or give vague definitions of defects.

"At mill-5000, we received a positive effect from the use of slabs of a lower quality group. It was proven (who would doubt it - note by Sergey P. Grigoryev) that a decrease in the quality of the billet is acceptable and does not have a serious impact on the quality of the products of the next processing stage. The finished product meets all requirements of the standards."