Myron Tribus, The Germ Theory of Management

“Like all people, they resented the need for change and hoped in their hearts that it would all go away.”

Source: The Germ theory of Management / Myron Tribus, director of Exergy, Inc. (translation by Yu.T. Rubanik).

Free access to articles does not in any way diminish the value of the materials contained in them.

Myron Trybus draws an analogy from 19th (19th) century medicine and 20th (20th) century government to illustrate why society adheres to dominant paradigms and resists change in order to improve our lives. – Approx. S. P. Grigoryev.

Introduction

William B. Gartner and M. James Naughton, in their recent review of Deming's management theory, wrote:

“Medicine has been used ‘successfully’ even in the absence of knowledge about microbes. The health of some patients has improved, others have deteriorated, and others have remained unchanged; and in each case the result of treatment can be reasonably justified.”

Doctors prescribe treatments for their patients based on what they were taught in college and practical experience. They can only apply what they know well and believe in. They have no other choice. They cannot apply what they do not know or do not believe. What they do is always interpreted as actions that are known to achieve a goal. As professionals, they find it difficult to deviate too far from generally accepted knowledge and beliefs. They are under the pressure of "generally accepted practice". From this point of view, doctors are no better and no worse than the rest of us. We are all prisoners of our upbringing, our culture and the level of knowledge of our teachers, educators and colleagues. Today we smile when we read that when suturing a wound with silk thread, surgeons 150 years ago recommended leaving a piece of thread outside the wound to drain pus, which necessarily appeared due to an unsterile needle and unwashed hands.

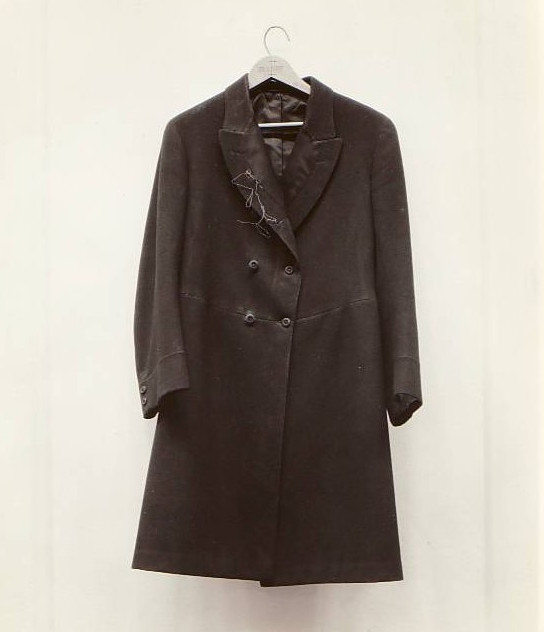

Photo. 19th century surgeon's coat with needle and thread for lapel surgery.

- Margaret Hurowitz, Chief Historian, Johnson & Johnson.

Doctors had a theory about how malaria spread. They called this disease "mal-aria" (bad air), emphasizing that it was caused by unhealthy night fumes. Their theory encouraged people to look in the wrong places and find the wrong answers to solve their most pressing problems. Today our managers do the same. When they face intense competition in the global market, they try to change economic policies, tax structures, trade policies - anything other than their own understanding of how to make the company competitive. They ask questions about anything other than their own management theory.

It's not easy to change people's beliefs

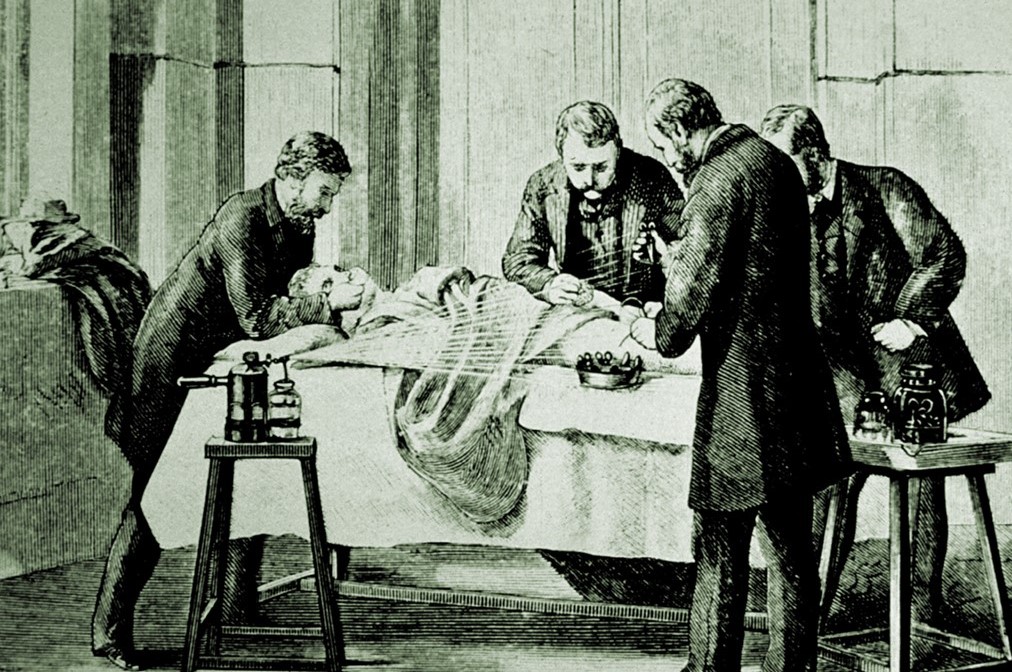

Try to imagine that it is 1869. More recently, Pasteur demonstrated that fermentation is caused by airborne organisms. Just a few months earlier, Lister had tested the first antiseptic, carbolic acid, and found that it prevented inflammation and pus formation after surgery.

Engraving. Use of Lister's invention, carbolic acid through a nebulizer.

120 years ago, medical information spread much more slowly than it does today. Imagine that you are a young researcher at one of the US medical colleges. The Civil War has recently ended and you are trying to make a career out of the military, you are a serious aspiring doctor trying to learn the latest advances in the medical field. Suppose that you have just learned about the work of Pasteur and Lister and that you are invited to speak to a group of famous surgeons, many of whom gained fame for their heroic service during the American Civil War. Through self-education, you have come to the conclusion that these famous, distinguished surgeons are actually killing their patients. Your job is to explain to them, if you can, that they are "attaching death" to every wound because they don't wash their hands or don't sterilize their instruments, you have to convince them to forget almost all that they had been taught, they left behind much of the experience they had accumulated over the course of their careers and restructured their understanding of medical practice in light of the new theory of viruses. Can you do it? Can you convince them? Do you think they will be happy to listen to you?

Let's now assume that you are a listener rather than a speaker. You are one of the qualified doctors who enjoy well-deserved respect in your town. You have a beautiful house on the hill, a beloved wife, a beautiful carriage, thoroughbred horses and several servants. You are part of the elite of society. How would you feel if someone began to spread the word that the treatments you were using were a threat to patients, that the theories you espoused were nothing more than buzzwords, and that you were in the habit of examining them from patient to patient? unwashed hands guarantees the spread of infection to everyone who happens to be your patient? What do you think will happen to your practice if these types of rumors start to spread? How would you feel about their distributor?

It's not 1870, it's 1989. And you're not a doctor. You are a respected professional. For most of you, management is part of your professional responsibilities. You approach management according to what you have been taught and learned throughout your career. I have worked among these types of people and I know that you have an explanation for everything, no matter what happens. I would be shocked and delighted if you explained your recent failures in, say, the following way:

"You know, I really don't know what I'm doing and I think most of what I know is wrong." You are the same as I was more than ten years ago, working as an administrator in industry. You will not achieve success if you constantly doubt the validity of what you believe. And of course, you will not achieve the desired result if you talk about your doubts about what you know and can do. My problem is similar to that faced by a young doctor who was trying to introduce the theory of viruses into medicine. There is a new theory of management, as different from the one that most of you now trust as the theory of viruses is different from what doctors once trusted. For reasons that will soon become clear, I call this new approach "viral theory of management."

Not everything the doctors did was wrong, but almost everything! Before the advent of the virus theory, they interviewed patients, wrote medical histories, prescribed changes in diet and lifestyle, and delivered babies. They developed a sense of social responsibility. They were sincere in their efforts to do the right thing. Read, for example, the Hippocratic Oath, which predates the virus theory by many centuries. Even the earliest doctors did their best with what they knew at the time. This is exactly what you do. What doctors were taught was not good enough, and sometimes downright dangerous and harmful. But they learned. And you can learn. Medical practice has changed under the influence of virus theory, and management practices must also change. These changes are already happening in different places, in different enterprises. The result of these changes is a healthier, more resilient and efficient production organization.

In this fiercely competitive world, unhealthy businesses will have to die out, those that continue to operate according to old methods will have to disappear. This is not a new fad that you are free to follow or not as you see fit. The problem I'm talking about is urgent. Your career will depend on whether you are willing to learn new ways of working. I don't expect everyone to like it; doctors at one time didn't like it either. But it was so - so it will be!

Fundamental changes are required in management

As I mentioned at the beginning of this conversation, in 1865 Pasteur was sent to the south of France to investigate questions about what kills silkworm caterpillars. It was there that he isolated the bacilli of two viruses and developed methods for preventing infectious diseases. That same year, Lord Lister applied similar ideas to medicine.

In the 1920s, Walter Shewhart of Bell Laboratories was tasked with finding out what could be done to improve the reliability of telephone amplifiers used for long-distance communications. It was required that these amplifiers be located at least one mile apart from each other and be part of a communications system with underground cables. Unlike doctors, Bell System wanted to be sure the amplifiers were working before they were buried in the ground. In case of any malfunction, they would have to be dug up. The amplifiers included vacuum tubes, the operating time of which was known to be indefinite. Shewhart needed to figure out what could be done to ensure the amplifiers would work underground. While working on this problem, he discovered the variability virus.

Shewhart discovered something that should already be clear to everyone. Let's say you make vacuum tubes. Every component that goes into one of these is exactly the same as any other lamp. Then you assemble a device from such lamps in the same way. Then, if the lamps operate under the same conditions, then their operating time should be the same. The problem is precisely that it is impossible to produce lamps of identical quality. This is due to slight differences in the chemical composition of the starting materials, inaccuracies in the production process; In addition, at all stages there is random contamination. In short, the existing variability leads to uncertainty in the lamp's uptime. If the assembly process itself is clearly not controlled, then some lamps will obviously not last long. They are victims of the variability virus. This was the discovery made by Shewhart.

His research led to the concept of statistical quality control. In other words, like Pasteur's work, Shewhart's discovery laid the foundations for the "viral theory of management."

Few people understand how production variability affects manufacturing costs. Even fewer people have any idea what can be done in this regard and what the role of management is here. Just as Lister recognized the broader implications of Pasteur's work in the medical field, so Dr. W. Edwards Deming saw the relevance of Shewhart's work to general management theory. Moreover, Deming was not alone. Homer Sarasohn and J.M. Juran were also pioneers of this trend. They realized that the key to better management was to study the processes by which products were produced.

If sources of variability are eliminated at each stage of production, the result will become more predictable and, therefore, production will be more manageable. It will be possible to speed up production activities by reducing downtime and delays. Thus, the main idea is to eliminate the virus of variability and therefore improve the reproducibility of production. This idea was realized during the Second World War, thanks to widespread training, which had a huge impact on the success of the giant American war machine.

In 1956, several Bell System specialists embraced the idea so well that in the introduction to Western Electric's Manual of Statistical Quality Control they wrote: "...methods of process capability research are applicable to virtually any problem: technical , engineering or management nature, as well as quality control."

Unfortunately, most of our managers after the Second World War were so busy getting "quick" money that they forgot about the virus of variability, and this theory was forgotten in America. And none of our business schools have picked it up. On several occasions, when I myself tried to introduce the concepts of this theory to students at prestigious American business schools, I was only listened to politely (if at all).

Viruses are invisible. That is why they are so dangerous, they are extremely difficult to detect, and so difficult to cure. You will only know about their presence by the presence of symptoms. The situation is exactly the same with viruses of variability - they are invisible. To fight them, you must know where to look and how to look. Just as doctors often must use special tools and even take tests, managers must learn to collect data and analyze it in a certain way. Dr. Deming says understanding this data requires "deep, thorough knowledge."

An experienced doctor examines your throat and says: “I think you have an infection!” or “Have you eaten chocolates recently?” He examines your tonsils and listens for sounds in your lungs. But if he does not understand the viral theory of diseases, he cannot correctly interpret these symptoms.

In the same way, an experienced manager dealing with the virus of variability can judge the health of the enterprise by analyzing the data received, asking questions, evaluating the answers to them, and listening to discussions in work meetings. If a manager is aware of how this virus manifests itself, he will understand what he sees and hears. Otherwise, he will be as helpless as doctors were many years ago, who prescribed various breathing procedures against mal-aria.

Variability is a virus of systems

First, doctors had to learn that viruses, although invisible, could be transmitted from one patient to another in a variety of ways. They had to believe that viruses really exist. They had to learn about sterilization and antiseptics. They had to get used to the idea of having to wash their hands. Finally, they had to study different cultures of viruses and the diverse causes of infectious diseases. In short, doctors were forced to form a new understanding of the world.

You will have to do the same. Let me give you one example: Consider a business that purchases castings (or even has its own foundry). Metal castings are subjected to sequential machining carried out on various machines. The various machined parts are then assembled into a product in which the parts perform reciprocating and rotating movements, presumably with a certain accuracy.

We know that the metal produced by a foundry is not completely uniform. There are always some differences in the composition and processing methods of the metal. The technological process in the foundry also has some instability. We can say that all these processes are infected with the virus of variability. As a result, we obtain castings that vary in composition, size, hardness and structure. Moreover, different hardness and structure occur not only in different castings, but even in different places of the same casting.

When such castings are submitted for machining, this virus of variability soon infects the machines. Differences in hardness, for example, lead to uneven wear on tools. In addition, it is difficult for the operator to accurately set the speed and feed. Tool wear becomes unpredictable, as does machine maintenance. Consequently, the infection has spread to the tool warehouse, where a larger stock of tools is now required to be stored than would be necessary if tool life could be accurately predicted. Now, tool inventories have also become subject to strong variability. The inability to predict maintenance needs increases the number of service technicians that must be hired and complicates the maintenance process.

The need to hire and train so many people at once overloads the training process and therefore not all of them are equally well trained. Consequently, the service system is also infected with the virus of variability. And the machine may fail much earlier than expected due to varying maintenance. Insufficiently trained workers do not follow instructions and maintenance procedures exactly. Thus the virus of variability from the service department penetrates into the personnel department, where personnel files indicate great differences in the attitude of workers to work, when in fact they are subject to uncontrollable variability. They are victims of a lottery, but neither the employees themselves nor the HR department understand this. The Variation Virus infects every part it touches.

Imagine a beer can company. It purchases rolls of aluminum sheet from a supplier, which, passing through a series of installations, are cut into blanks of various shapes, from which cans and lids are then stamped. Aluminum varies in thickness from roll to roll. When a new roll is inserted into the installation, it may become wrinkled, and then it will have to be readjusted. Now it is also unpredictable what will happen as a result of the installation. This means that the virus of variability has penetrated from the aluminum supplier to the installations. After a short time, some operators become particularly adept at handling these aluminum rolls. Since managers evaluate operators individually, in a competitive environment, people who have mastered new techniques do not always want to share them with their competitors. Managers think that the results they observe indicate a large difference in the abilities of the operators. So they want to get rid of the "worst half" of employees. They have no idea that their production is infected with the virus of variability, and act in accordance with their ideas. They have an explanation for everything. They are confident that they are doing the right thing. At the same time, they ruin the fate of some of their workers and therefore pose a danger to the prosperity of their enterprises. But since neither managers nor employees know anything about the virus of variability, being in the dark, they do not know what they are doing and do not want it explained to them.

Differences in components cause variability in the performance of the products assembled from them. The variability of finished products can be so great that only some of them do not have to be remade. Some products are so bad that they are only suitable for scrap, and at best can be disassembled and reassembled using other parts, which, in turn, may also be infected with the variability virus. The question of what to do with some of the “sick” products becomes an important point in the enterprise’s policy. Numerous meetings of managers are held, making their lives nervous and unpredictable. So, this very variability of source materials was allowed to infect all systems, including the management system and the managers themselves. The symptom is their stressed state, and the cause is the variability virus.

This contagiousness of variability, which spreads from machine to machine, then to service personnel and even penetrates into personal files, as a rule, is not detected by managers who are not familiar with the “virus theory”. They have their own views on life. The “treatments” they use may actually make the infection more contagious.

The examples above are taken from the manufacturing floor, but you will find them in the office and in the office. Out of gratitude to the Xerox Corporation, where I worked as an administrator, I will not go into detail about how differences in the maintenance of copiers can cause differences in performance and thus infect the entire office.

Let's say you live in a small town served by a small airline. Let's also assume that the airline's schedule is not very reliable, i.e. you cannot be sure that your plane will actually take off. The instability of the schedule leads to the fact that you are forced to go on business to other cities with a significant amount of time. Sometimes, to be on the safe side, you'll go a day early and be forced to pay for your hotel stay for that day. You do not risk leaving on a morning plane and returning in the evening. Imagine similar losses in all areas of society, and you have a recipe for a "cure" for a deteriorating local economy - these additional costs may be enough to, for example, cause your business to go under.

Too many people consider these delays to be “normal.” They just don't know how it really should be. Few of them are in countries where trains are on time, mail is delivered quickly, the telephone system works without delays, taxis are clean, and there is no trash on the streets. They are surprised by the presence of good health!

How much could be saved if there were no volatility at all? Let's look at just one example. In the early 1950s, the Henry Beck Company of Dallas, Texas, demonstrated how quickly it could build a one-story, two-bedroom home on a pre-laid foundation. As reported in Life magazine, less than three hours passed from the start of the build to the time the house was finished and painted, with one woman already taking a hot bath and another cooking dinner on the kitchen stove. Just think - three hours! The usual time is 30 days, and often more. But why does it take longer? Yes, because it is impossible to plan people’s work so accurately.

If a carpenter starts nailing a board a second after it is cut, instead of 15 minutes, the time spent will decrease by 900 times! Three hours will turn into 2700 hours. However, it is impossible to organize the work of people when building a house in such a way that only seconds are lost. We cannot expect here the precision of rocket flight or ballet movement. It is difficult to achieve such precision in production. But we can make every operation more accurate, and if we achieve this, then errors, miscalculations, defects, delays - all this will begin to disappear. As we eliminate the virus of variability, we will save time and money that we never thought about and that our calculation methods hide from us so skillfully that we consider these losses to be “normal.”

We are not used to thinking about achieving such precision of control that we can build a house in a few hours. It seems normal to us to wait half a day to be seen by a bank manager. The inability to schedule activities accurately means that for complex activities the time spent is 1000 times the time required. This is the price of the virus of variability.

It is impossible to completely get rid of variability. However, no one knows how much can be done! Until Sarason, Deming and Juran applied these ideas in Japan and the results appeared on a large scale, we were unable to appreciate that in many cases savings of up to 50% could be made. And we're not just talking about production. Sometimes the results in the service sector are even more impressive.

And processes can also suffer from immunodeficiency

Until doctors accepted the idea of viruses and began to analyze diseases from the point of view of the possibility of their infectious origin, they did not take into account the existence of the human immune system. Today, everyone knows that just a viral infection is not enough to make a person sick. Much depends on how the body's immune system reacts to viruses

Dr. Genichi Taguchi of Japan was the originator of the concept of robust design, in which variability not only does not increase, but rather tends to decay, resulting in good performance even when there is significant variability.

Engineers and managers who ignore basic statistics simply cannot bring themselves to think about how to design more reliable products and must waste dollars trying to control production processes. When managers spend huge sums of money to eliminate the effects of variability rather than learn how to reduce it, we call their approach "technology fix." If you can learn to manage variability and protect your operations from it while your competitors are spending millions of dollars on fully automated processes that can handle uncertainty, you will obviously be able to undercut your competitors' prices. Thinking in this way, we will understand why the NUMMI plant, equipped by Toyota for General Motors, is one of the highest quality plants, although the least automated.

Doctor or manager as detective

A common mistake doctors make is making an incorrect diagnosis. It is believed that, faced with a whole set of different symptoms, the doctor determines what happened to the patient. An experienced doctor understands the difference between a symptom and a cause. He knows what questions to ask to clarify the diagnosis. A doctor should be like a good detective. It is clearly no mere coincidence that Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was a doctor before becoming a famous writer, and that Sherlock Holmes was based on a professor of clinical medicine who believed that a careful examination of a patient could reveal a lot about his habits and lifestyle.

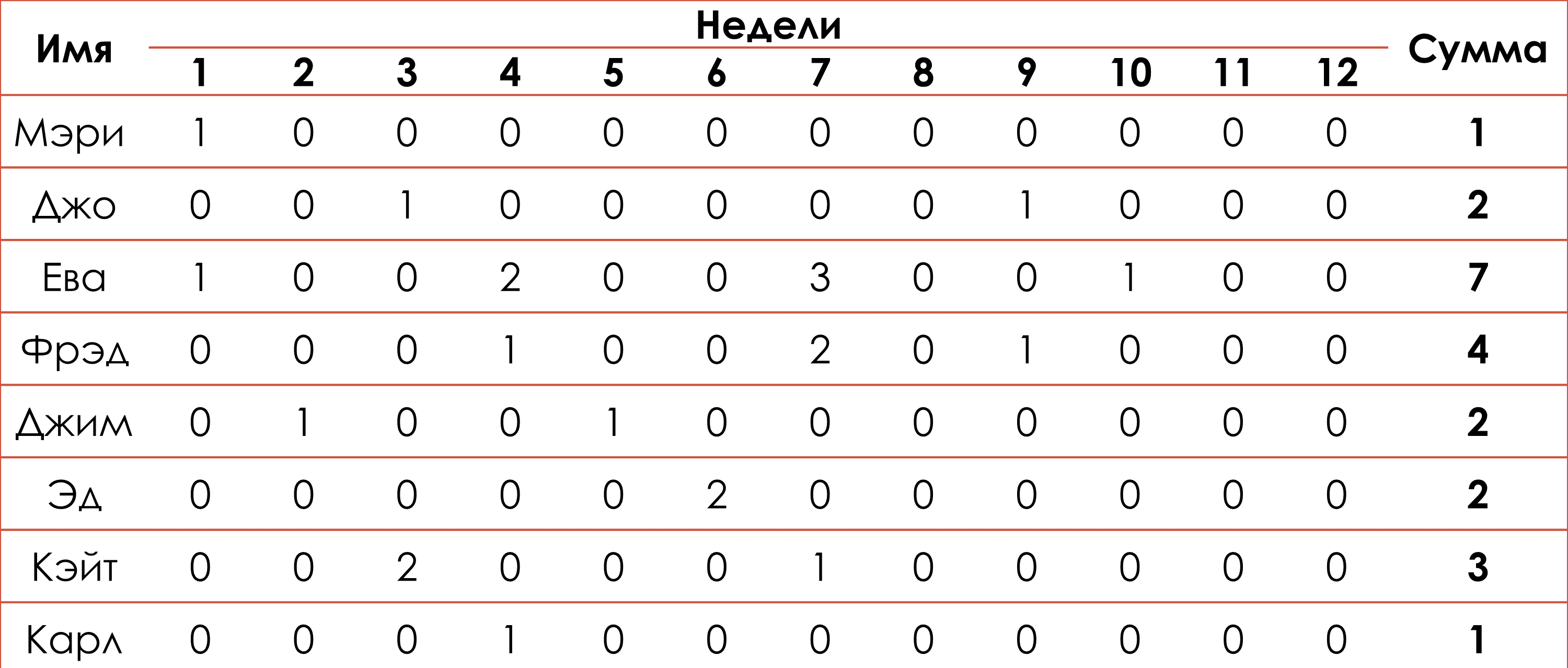

Try to imagine yourself as a doctor examining a patient. Below is 12 weeks of data for 8 workers making the same product and working at the same speed. What can you, as an experienced physician, learn from this information? What orders will you make? How to follow your instructions? If you were in charge of these workers, what would you do? What improvements would you make?

Rice. 3. Table of the frequency of production defects by employee (pcs./week).

I have demonstrated this chart to audiences in the US, Mexico, Canada, Australia and the UK and always received the same reaction. Usually they suggest having a good talk with Eve, putting her to work next to Mary, or asking Mary to help her. They also propose to fire Eva or continue her training.

One astute statistician at a meeting of the Royal Statistical Society in London went so far as to note the 3-day periodicity in Eva's work and suggested that this be taken into account.

After listening to various common sense recipes offered by the audience, I explain to them that the numbers presented in the table were actually generated by the random number generator on my computer. The defects were generated and labeled in memory cells to which I assigned human names. In other words, the reject frequencies were entirely generated by the system.

Only in 2-3 cases out of a thousand people did anyone actually believe that perhaps the problem was in the system itself, the system was infected with the virus of variability, and that it was not the fault of the workers. In the last four years, only three people have suggested looking at table data analysis as a means to see how predictable Eve's output is given system variability.

So, the process itself is infected with the virus of variability. If you don't start to "sterilize" the process, that is, reduce its variability, it will definitely infect workers. And not just workers. It will affect your ability to correctly understand problems.

People change their minds very slowly. I'll never forget one manager who said, "Look. I understand the numbers are computer generated. But I'd still talk to Eve!"

The results of workers' labor are influenced by the accidents of the production process, which they cannot control. Suppose that the foreman, in order to convince his employees to work better, decided to hang this table on the notice board. Naturally, we do not expect workers to understand the viral theory of management. They may think that such results are a consequence of their mistakes, and will try to do better. What, you don’t see how the variability of the system will affect relationships in the team and perhaps even affect the personal lives of workers? If the master does not understand this theory, you do not realize how the control system is infected? Suppose there is a system of annual assessment of foremen, and the data from this table is available to their managers. Let us also assume that the executives do not understand the virus theory and therefore believe that the master should take drastic measures against Eve. Let us finally assume that the master knows about variability and understands that it is the system that needs to be improved. Realizing the inadequacy in understanding approaches to the problem, how do you think the manager will evaluate the master?

I am not offering a detailed description of industrial relations. I am only describing what happens every day in factories, offices and offices all over the world.

Variability in the product manufacturing process also infects the supply system; The increase in the number of required spare parts is causing fever for it and its support services. Thus, we saw the virus of variability spread from the foundry and HR departments all the way up to the highest levels of management.

The meaning of what I want to say is very simple: variability is a virus. It infects every process it comes into contact with. Juran captured the essence of the spread of infection in a statement known as “Juran's rule”: Any problem is 85% determined by the system, and 15% determined by the worker.

The instinctive reaction of most managers I have met is to reproach the employee. But sometimes there are managers who, when faced with a problem, believe that they are to blame for its occurrence and could do something to eliminate it. As a consultant, I often had a hard time convincing these people that it was actually the system that was causing the error. Most managers will persist in thinking that people need to be changed, when in fact it is the system that needs to be changed.

Who should be responsible for cleaning these processes, in other words, for “sterilizing” them? Causes of variability, like viruses, are everywhere. Sterilizing the process will require someone to study the reasons behind the variability and eliminate them one by one. Only managers are authorized to make changes to the system, and if you are not personally involved in this, then the work will not get done. Your production as a whole will be in a fever. As a manager, you cannot absolve yourself of responsibility for the quality of management of production processes for which you are responsible. And if you can shift this responsibility onto someone else, then do we need you?

Some myths of managers

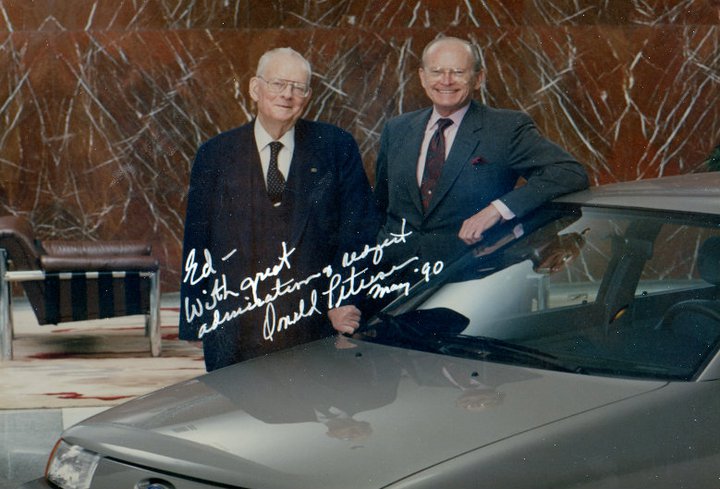

In support of this new approach to management, Don Petersen of Ford Motor Company outlined it to his subordinates as follows:

“I hate to tell you this, but sometimes some of you received promotions once or twice undeservedly due to the fact that the results of your work were incorrectly assessed. I have accumulated several management myths, which, I am sure, should be gotten rid of. I am aware of is that many of you will be deeply indignant. This is to be expected. Either you will cope with this feeling, or you will be left aside by those who understand all this."

The Harm Principle: If you try to improve a system of people, machines, and methods by setting quantitative targets to improve the performance of individual parts, the system will fail you where you least expect it, and you will pay for it in full.

This idea is difficult for people who are accustomed to thinking that the control scheme determines how production is carried out. They prefer to give clear orders to subordinates. They think they can divide the system into parts along the lines of the control circuit. A typical control scheme sits in their heads.

Their management strategy is “divide and conquer”. They talk about management the same way as some of my Dutch friends.

Drawing. Rice. 5. Hidden assumptions ingrained in the minds of many managers. The people at the bottom of the diagram are headless. (Courtesy of MANS Organization from Holland).

The system of concepts and views of many managers is too limited. They forget that work proceeds “across” the organizational chart, more or less perpendicular to the lines of subordination. They are not aware that different stages of the production process infect each other. They ignore the fact that they are dealing with the system as a whole. They are determined to judge each person and unit only by their deeds. They don't know how to recognize and define a process system.

They don't understand what is meant by process. They do not know how to determine when a process occurring “across” the lines of the control circuit is out of control. They insist that products are manufactured in accordance with the control scheme, when in fact they often do so in spite of it.

In some organizations, this method of management leads to the fact that departments become hostile to each other. They would rather interfere with each other than compete with each other.

If we consider this problem from the point of view of the management structure, without taking into account the need to use the general intellectual potential of the majority of workers, then it lies in the fact that work proceeds “across” the organization. Let's say you set a task for the production department employees to produce a certain number of products every month. Then you set your task to the sales department to implement them. Of course, it plays a significant role for the company whether the products arrive at the same time, or whether they arrive periodically and gradually. The possibility of predicting the release of products also has a certain significance. In other words, even if each person performs on average the required work, variability in performance will lead to additional costs and waste in other departments.

Consider, for example, loading a ship. The goods arrive at the dock by truck and are unloaded by hand. The longshoreman then hooks it with a crane. The cargo packages are lifted and placed on the ship's deck, where another loader picks them up with a lift and sends them into the hold. My colleague noticed that other ships of Columbus were loaded in this way: Nina, Pinta and Santa Marie. If you observe this process, you will see that variability in the size of the cargo, its movement during loading, as well as variability in the work of people and machines, creates time delays. And even setting individual tasks for each worker will not speed up this process, but may slow it down due to the fact that each performer will try to look better at the expense of others.

The same problem arises whenever people must work in sequential operations, be it accounting, sales, repairs and maintenance, or customer service. Work goes “across” the enterprise, and attempts to break it down into separate operations only lead to losses and unnecessary costs.

Sometimes variability is so inherent in a system that it cannot be improved, but only completely redesigned. This is why container ships are so widely used. By shifting the inefficient labor of packing cargo to someone else, we eliminated the variability of the loading process. The time it takes to fully load ships has decreased from several days to several hours.

If you assign tasks to workers at the lower level of the system, or even the middle level, without regard to the system aspects of production, you are not fulfilling your responsibilities. Remember what you tried to do with Eve. Don't do this to everyone.

Managers' jobs have changed

People work in the system. Managers must work on the system to improve it with the help of people.

There are several key words in this statement.

"They work in the system." If you accept this, then you also have to accept that workers cannot control what happens in the workplace. This type of management, where you tell people that they are responsible for the results of their work, is at odds with your own ideas. When you do this, you contradict yourself. Of course, you will object: “If you don’t ask the employees, they won’t do anything at all!” This is not true, but what is more important is that you must make it their responsibility to help you improve the system.

"Managers must work." What did you think your job was before?

"Work on the system." Do you know how to identify the system you are supposed to be working on? Do you know how to work on the system? Do you realize what you need to learn to do this? Do you know where they teach this?

"To improve it." Do you still adhere to the rule: “If the system isn’t broken, don’t rebuild it”? Did you know that you need to spend about a third of your time worrying about improving the system? Is this what you do? Do you think this is what you should do?

"With the help of people." Do you like the idea of employees helping you? Do you think you should train them to help you? Do you want this help? Do you have any concerns about this assistance? Do you know what to do to get this kind of help?

State of health of the enterprise

This audience, of course, is not the same as it was a century ago. It consists of enlightened people. Naturally, you will not act like doctors of the last century, when they were told to monitor the sterility of operating rooms. They resisted with all their might:

“What, wash your hands too? Leave me alone! I have more important things to do.”

A lot of work has been done to change their habits. This required doctors to recognize how much they had to learn and study. Like all people, they resented the need for change and hoped deep down that it would all pass.

They alone would not be able to cope with changes in treatment practices. At first, they needed the help of nurses and orderlies. They themselves had to first understand the viral nature of diseases. It's one thing when you learn a new theory as a young medical student, but quite another when you earn your daily bread as a practicing physician. Once doctors had mastered the new theory, they had to teach medical staff how to sterilize instruments and other equipment. They couldn't just ignore it. They had to introduce new work practices and train their employees in them. They had to monitor their learning so as not to repeat the same thing several times. Changes like these don't happen quickly. Many patients had to leave this world as these changes slowly made their way into medical practice. The history of medicine is replete with examples of doctors fighting new practices and even ridiculing those who followed them. They hid their mistakes, and only a few people outside of medicine knew what was happening.

And today I constantly meet managers who do not want to learn. They are too busy with mergers, acquisitions and business closures. Having false ideas about how an enterprise should be run, they constantly make demands on their workers and, thus, provide jobs only for union leaders.

Even if you are personally convinced that a different management theory needs to be adopted, you will quickly discover that you cannot apply it alone. You report to your boss, and if he doesn't keep up with new ideas, you risk jeopardizing your job. You will have to make difficult choices. If you do not occupy a high enough position in the company, you are guaranteed to be depressed.

The most common request I received was: “Could you come and tell our first managers about quality?” To this I always have a ready answer: “Sorry, but I don’t do such things. However, you can contact my colleague who will accept such an invitation. His name is Don Quixote.”

We looked at an example related to manufacturing, but the variability virus infects any system it touches. This also applies to management itself. As you know, doctors themselves can get sick. If you work in a plant infected with variability, the disease will spread to you. You won't enjoy your work. You will have to work hard just to keep things going as usual. If you do this type of work for too long, you will quickly burn out.

Perhaps, with the help of people in the financial community, you have tried to divide your company into separate "profit centers", assigning a performance rating to each. Each employee of your enterprise has a well-defined task, and he bears full responsibility for it. However, whether you like it or not, the enterprise as a whole is a single system. You can divide it up any way you want in your head; in reality it is what it is - a highly interconnected complex system in which each unhealthy area infects the others. If you ignore this basic fact, the system will never be healthy. It will never be able to compete with healthy systems. And if it is not artificially protected from competition, it will simply die. Your work will disappear with her.

Culture transfer

In my opinion, what our country needs most now is an understanding of what it means to be a leader. Don Alstadt described the situation in the United States with the expression: “Over-managed and under-led.” We must transfer the management of our enterprises to new management principles. We have a responsibility to lead the transition of our management culture from one norm to another. This transition began in Japan after World War II, as a result of the intervention of Homer Sarasohn. It accelerated after the arrival of Deming and Juran and continues to accelerate to this day. In the early 1980s, some companies became aware of the Deming Prize and the impact of quality management on Japanese industry. We now have examples of companies from many countries around the world showing what it means to change the culture of production.

I just want to tell you, based on the experiences of others, the path that most of you are likely to follow in changing the culture of production. Once you take this path, you have to go through seven stages. My own observations confirm the validity of the data in the table originally compiled by Professor Tsuda.

Stage 0

Managers express concerns only about the market, profits and profitability.

Stage 1

Managers are concerned about product quality because of its impact on warranty costs and customer complaints. The shrinking market is becoming obvious. The measures taken are to increase the number of inspectors to prevent the release of bad products.

Stage 2

Managers realize that controlling the production process leads to reduced losses and lower costs for obtaining an acceptable level of product quality. Efforts to improve quality management are supported in manufacturing.

Stage 3

The results of quality control do not apply to the quality of work, so managers begin to implement quality management. Statistical quality control is introduced in production.

Stage 4

Managers require the use of statistical quality control and quality management methods in all departments related to production (supply and transportation departments, warehouse, etc.).

Stage 5 (difficult stage)

Managers try to convince R&D, engineering, and economics departments to adopt quality management principles, but these departments feel that the problem is not their concern. Gradually, all these specialists will understand that quality is their business.

Stage 6

Managers are beginning to recognize that the principles of quality management will only be useful if they are applied to all parts of the enterprise, but they do not know how to achieve this. They organize actions throughout the company to see what needs to be done.

Stage 7

Managers proclaim (and act on it) that: “Firm-wide quality management is company policy.” This means in particular:

- Quality comes first;

- Decision criteria are consumer-oriented;

- Respectful and humane personnel policy;

- Coordination of activities of all departments;

- Cooperation of all departments;

- Involving all employees in the process of improving the system;

- Strong relationships with suppliers;

- Effective relationships based on evidence and statistical quality control.

Checklist of what managers need to learn

Every manager should understand basic statistics:

- Process flowcharts.

- Ishikawa fish skeleton designs.

- Checklists.

- Histograms. Pareto charts.

- Scatterplots (graphs).

- Control cards.

- Basics of experimental design.

Every manager must learn:

- Recognize, define, describe, diagnose and improve the system for which he is responsible.

- Diagnose the nature of system variability and decide which variations are special and require special actions, and which are general and will require changes in the design and operation of the system. The manager must be able to distinguish the useful signal from the noise.

- Lead groups of people with varying levels of education in identifying problems, collecting data, analyzing them and developing proposals for their resolution, elimination and subsequent verification.

- Diagnose people's behavior and distinguish between those difficulties that are caused by differences in people's abilities (15%) and those that are caused by the system (85%) [Juran's rule].

In the last years of his life, Dr. Edwards Deming gave a new estimate of this ratio: 2% to 98%. - Note by S. P. Grigoryev

"A leader's primary responsibility is to build the trust and respect of those he leads. A leader must himself be the best example of what he would like to see in his followers."

Conclusion

Now the country is absorbed in the struggle for its existence. Its industries are being undermined one after another. Since the economy is experiencing difficulties, it does not provide the government with the necessary budget revenues. This, in turn, leads to cuts in spending on various programs, including defense, since the government cannot afford them. The only way to survive is to learn to manage resources better. It's your job to learn how to manage properly, how to manage quality.

Let me close with a short story I heard from New York Times columnist Roger Baldwin:

“Once upon a time, a heavyweight boxing match was held in Madison Square Garden. As is customary, several preliminary fights were held before the main fight. In one of the preliminary fights, the boxers clearly did not match each other. In the first round, one of them fell and could not get up. In the gallery someone shouted: “Fraud! Deception!" Soon the hall was shaking with shouts: "Deception! Deception!" And still the boxer did not get up. Finally, a stretcher was brought and he was removed from the ring. And people continued to shout: "Deception!" The next day this boxer died.

You understand - the young man had to die to prove that the fight was carried out according to the rules."

I hope that this nation will not have to die just to prove that the struggle that is now taking place is being fought according to all the rules.

“Resistance to knowledge is still strong in people. The type of transformation that Western (read, Russian – Note by S.P. Grigoryev) industry needs involves expanding knowledge, and yet people continue to resist them.

Pride is not the last factor in this struggle. After all, new knowledge that comes to the company can reveal our mistakes. The best approach is to pursue new knowledge because it can help us do better."